Sample the sonic world of the Second World

Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture.

Click to listen to Chimurenga’s FESTAC ’77 mixtape while you read.

Ntone Edjabe, Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi

Dec 9, 2020

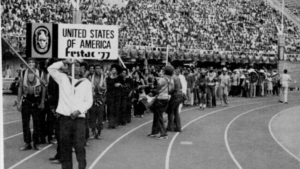

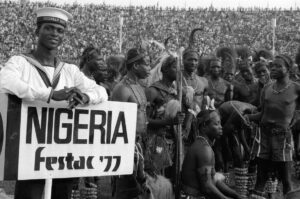

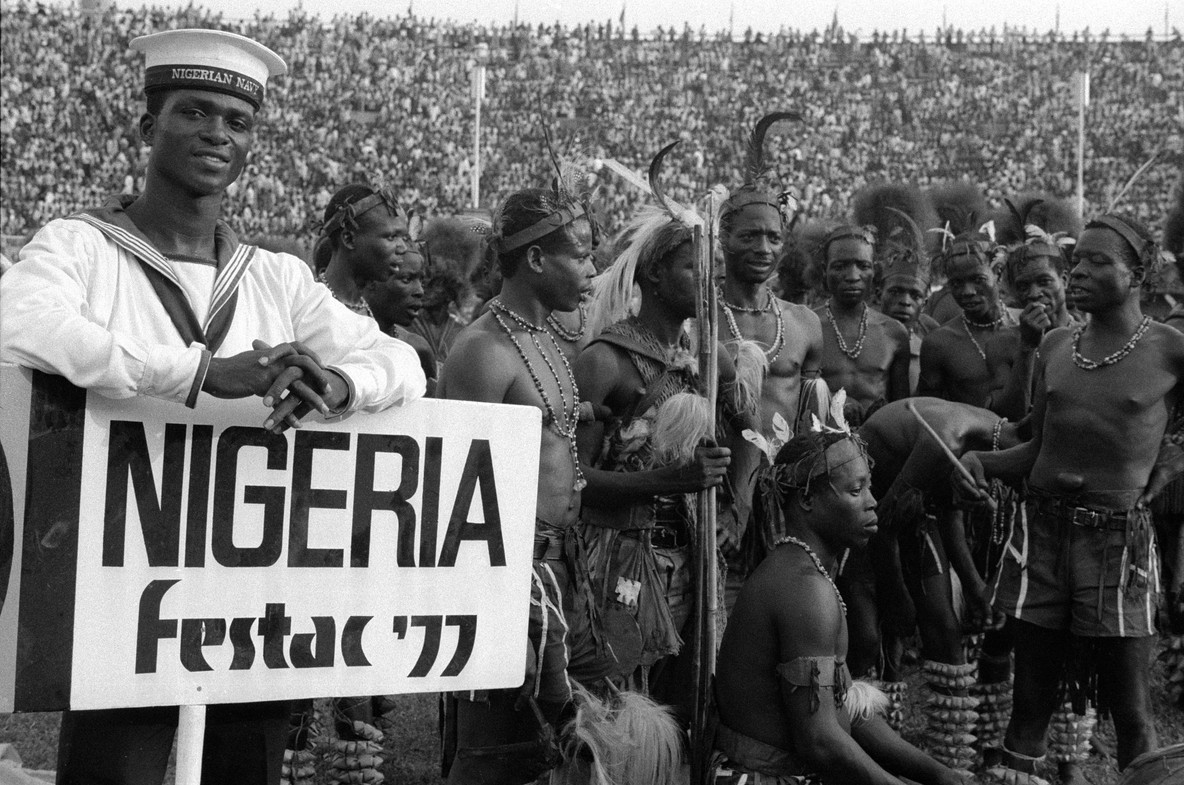

The Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC ’77). Image © Marilyn Nance

Click to listen to Chimurenga’s FESTAC ’77 mixtape while you read.

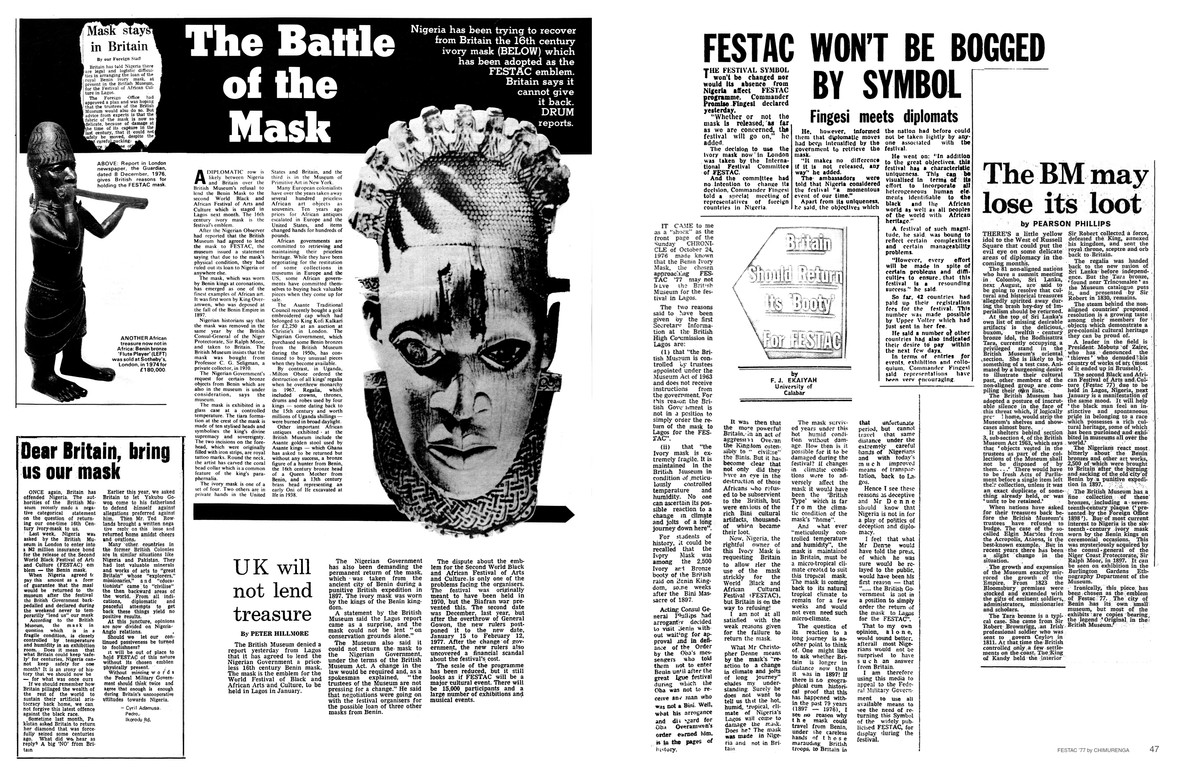

I’d say the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, otherwise known by the acronym FESTAC ’77, was the most important cultural event in the Black world in the 20th century. It was staged as its cultural Olympics, and dwarfed similar events that had come before and anything that has come since. On January 15, 1977, FESTAC opened to much fanfare in Lagos, Nigeria’s economic hub and capital city at the time. It included a parade by participating countries, dance performances, cinema, music, literature, and art exhibitions. The aims of the cultural fiesta were ambitious: to represent the breadth of Black and African values and culture, to model mutual coexistence with the other cultures of the world, and to position Africa as the original homeland of African diaspora peoples.

This landmark event is the subject of the recent publication FESTAC ’77, the product of years of research helmed by *Chimurenga*—a magazine based in Cape Town, South Africa, and one of the most important cultural journals on the continent—in collaboration with Afterall, the London-based journal. Mapping and sampling are tools that Ntone Edjabe employs as both the editor-in-chief of Chimurenga and as a professional DJ. He uses this approach to extraordinary effect as the editor of the FESTAC publication and compiler of the accompanying FESTAC mixtape. In the book’s colophon, the terminology he employs is that of refusal—a refusal to arrange and compose, a refusal to settle. There is an aesthetics of disruption at play; of making something more complex; a mode that requires a different kind of listening (and reading), which goes against smoothness and embodies the multiplicity and discordance that was also at the heart and spirit of the Pan-African gathering. For Edjabe, all material is susceptible to manipulation. There is a pliability to vinyl and a texture to tape. The one you can scratch, the other you can unravel. He approaches the FESTAC archive and the material within—in its full visual, sonic, and written dimension—as a DJ and sampler, altering its forward narrative, singling out phrases, beats, or sections to work as new loops, new patterns of sound, bringing hearing to the unheard, teasing out its archival hauntings.

The FESTAC mixtape is an incredible compilation of spoken words, recitations, interviews, and music. The idea is not to present a neat sum total of the FESTAC experience. Instead, listeners or readers are provided snippets that may help them to come to their own understanding of this historic event. To accompany and contextualize your listen, I discussed the project with Edjabe.

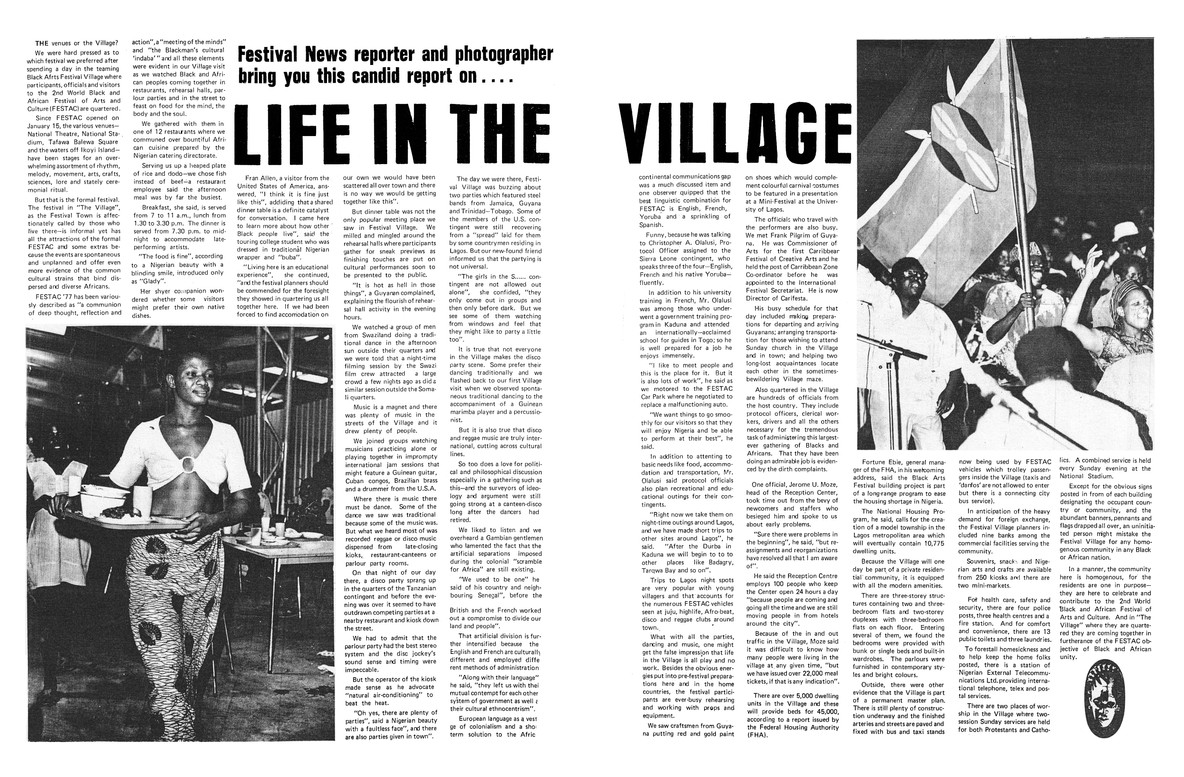

Detail of the FESTAC ’77 book by Chimurenga

—Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture

Ntone Edjabe and Smooth Nzewi would like to thank Nancy Dantas, C-MAP Africa’s inaugural fellow, for her role in facilitating this conversation.

Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi: In order to compile the FESTAC book (2019) and mixtape (2020), several years of research across continents was required. Can you translate the scale of this endeavor? Where did you find materials and what were their conditions?

Ntone Edjabe: My first encounter with the memory of FESTAC was as a student at the University of Lagos during the early 1990s. The University of Lagos, Akoka, situated in the Lagos suburb of Yaba, had been one of the festival’s main sites, along with the National Theatre, the National Stadium, and FESTAC Town, the festival village. These structures were built specifically for the festival and constituted a significant portion of the city’s built infrastructure after. But the event itself felt very distant, inaccessible; Lagos was a different place and these buildings were like monuments to a vision long-gone, and variously described as a blessing or a curse. FESTAC came back into my consciousness years later, in 2005, though a short fiction by Akin Adesokan, a friend and longtime collaborator, who incredibly reimagined it as a festival curated by Esu Elegba, the Yoruba trickster god, and delved into art piracy and the so-called curse of FESTAC.

Our push to collect and produce material on FESTAC and other festivals came after South Africa’s World Cup in 2010, which was billed as “Africa’s First World Cup,” and reproduced the image of Africa as some sort of game reserve. By that time we’d launched the Chimurenga Library as a tool to produce long-term research collectively while going on with our everyday work. It meant that every project, be it an issue of the Chronic or a music performance, would contribute somehow to a larger query periodically installed in the Library. For instance, an issue of Chronic on cartographic representations of Africa would be an opportunity to study the regionalism at play at FESTAC. Or a DJ performance would be used to explore FESTAC’s archive in popular music. We haven’t only been doing research on the festival, but it became part of a library from which we would draw the grammar for other work—along with Franco Luambo Makiadi (the DR Congo’s music megastar), football, literary magazines, Fela, Miriam Makeba, dub poets, popular comics, and others.

There is an official structure in Lagos, the Centre for Black and African Arts and Civilization, which was founded during the Olusegun Obasanjo regime in 1979 to act as custodian of the FESTAC archive. So, there is an official story, produced and preserved by the Nigerian state. The scholar Andrew Apter has produced a good analysis of this material and I am sure many more will follow. Our project, as always, was about how knowledge circulates.

Detail of FESTAC ’77 book

Our aim was to assemble an archive of Pan-Africanism through the FESTAC years, roughly 1971–79. We wanted to tell these stories through the thousands who shared space in FESTAC Town, the artistic village built for the festival, in Lagos, for one month, and the forces that got them there.

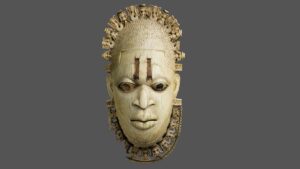

We wanted to circulate or recirculate writing, images, sound, rumor that an event of this magnitude would produce, not only about itself but about the world. To hear the poise of Sun Ra, the experimental jazz composer and pioneer of Afrofuturism, in an interview after his first performance in Nigeria, in which 5,000 people walked out. Ra spent his life announcing the end of the world in soft tones, warning about what will happen when “they” switch that button. By 1977, Lagosians had developed an appreciation for high theory combined with impassioned preaching—but served with the funk—and people expected Afropessimism to be danceable. In other words, Lagos of 1977 might have been farther out than Saturn. But our research was never a relentless chase for archival material—FESTAC was what it was. I am more interested in what it could have been. When we couldn’t find archival material on one topic, we encouraged contributors to write in the present-tense of the event, to recover memory through fiction like Toni Morrison does with Beloved. For instance, the trauma of the infamous British punitive expedition in Benin of 1897 resurfaced through FESTAC. Sure, we could scan the British archives to trace how the loot from that expedition was dispersed across the world, and we did this. But the people of Benin, the Nigerians, had begun their own process of restitution through FESTAC, a process that was initiated by the Oba of Benin, Akenzua II. By proposing the mask of Queen Idia as the emblem of FESTAC, a mask that was stolen by the British during the 1897 expedition, the Benin artist Erhabor Emokpae put that process, and the question of restitution of African artifacts held in Western museums, on the world stage.

Detail of FESTAC ’77 book

There is so much postcolonial African, global Black, and world histories layered in what you have just said that need to be further explicated. I also find your process of thinking about the past through the present, or in present tense, very illuminating. It calls to mind the Derridean notion of “archive fever.” You are engaging the FESTAC archive, simultaneously archiving and producing the archive afresh.

Yes, framing FESTAC broadly as a container of world-making acts was also strategic. It required us to engage with every participant as a major player in world history—or at least in art history. You know, Africans never demanded to be a center of the history of capitalism. But we cannot ignore that every major technological shift for the last four centuries is connected to the Congo—its people, its soil, its waters. Our research focused as much on what people did before and after FESTAC, individually and collectively. This material isn’t available in any official archive. Reporters at FESTAC may have followed Stevie Wonder and Miriam Makeba, but few would have known of Werewere Liking, the Cameroonian playwright, or the Rwandan philosopher Alexis Kagame. So we could not respect state borders or archives, we needed to follow individual paths across the world.

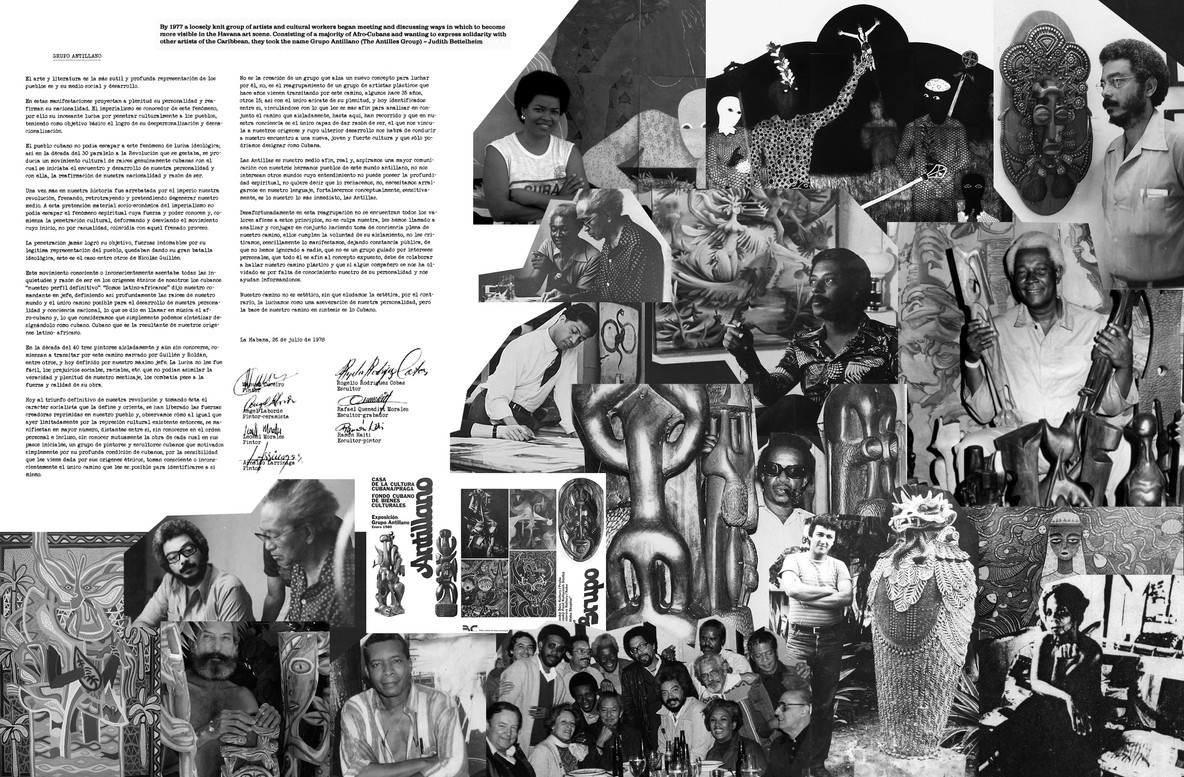

I think of Pan-Africanism as a theory and praxis of circulation. Its work is about “overcoming maps,” as you and your colleagues of PACA (Pan-African Circle of Artists) once put it. Which also means producing our own cartographies. It forces you to think of the world from a non-universalist perspective and new geographies emerge. For instance, most of Western Europe boycotted and even tried to sabotage the event, so Black people living there had to regroup into formal collectives in order to participate. How much FESTAC contributed to the formation of Black British identities deserves its own study. In Cuba, collectives like Grupo Antillano emerged from their participation in FESTAC. These new cartographies are based on our own circulation and networks—we decided that every place we visited would have been affected by FESTAC, and we mapped this effect. Our approach was more cartographic than archeological—to map movement, impasses, and breakthroughs. In SA we say, “Angazi, but am sure,” which means, “I don’t know, but am sure.” And you just keep moving—no timeline, no specific destination, just keep moving. You’ll know when you get there.

Detail of FESTAC ’77 book

To return to the mixtape, it is not a random mash-up. It offers a narrative of the FESTAC as a historical event but also a contextual experience: the contestations, arguments, disruptions, and the underlying politics of Blackness and emancipation rhetoric. You have described FESTAC as an opaque project. Can you elaborate on that, and also how that opacity unravels in the mixtape?

I think mixtapes operate in a similar manner as the FESTAC publication. The sole track begins and ends with the tape, but as a listener you find yourself in the mix, maybe through your interest in a particular artist, and build from there. It would be your entry point alone, or with the people you share a collective memory with.

The opening brief of FESTAC makes the event impossible to read as a whole, except for the organizers who had to write reports. Everyone else had fragments—from experience, memory. And that’s the archive we chose to work with. I’ve already mentioned the influence of Toni Morrison, especially with her work on *The Black Book*—her attempt to plug gaps through fiction, the collective writing that produced the book, a thematic organization that relies on the reader’s own knowledge to produce links or defragmentation, her decision not to index such an epic work. I could go on about this, it is such a conceptually rich text! Black archival work has produced plenty of methods, from Cheikh Anta Diop’s uses of the social sciences to Lee Perry’s decision to burn down his Black Ark, demanding that we preserve the void instead. And then of course you have Black music, where the past and future always seem present.

I admire George Perec and the Oulipo Group and their exploration of the creative potential of self-imposed restrictions. Like Perec’s Life: A User’s Manual, both the FESTAC book and tape are puzzles that you can begin at any point, but without the same desire or obsession for exhaustivity. What you have are in fact pieces from different puzzles. Sometimes you’ll get a snapshot that cuts through time, like National Ballet of Zaire, or people bound together in a specific space, like a flight from New York to Lagos via Madrid. Inside the plane taking the first contingent of African Americans to Lagos, Craig Harris, a 21-year-old trombonist newly drafted into Sun Ra’s Arkestra, his first trip abroad, takes the empty seat next to Minister Louis Farrakhan and a six-hour conversation ensues. Audre Lorde is writing the poem “Sahara.” Marilyn Nance, a young artist recently graduated from Pratt Institute, has begun building what would be the largest photographic archive of the US delegation at FESTAC. There are over 300 passengers on that plane. In the time of the event, I’d imagine that all these narratives would constantly encounter obstacles—linguistic, for example. Imagine all these different peoples living together in a single village, along with 60 other delegations! Continuities aren’t really possible, all you have is relation. So opacity is a built-in component of FESTAC.

We open and close the mixtape in the time/place of FESTAC, with Sunny Ade’s performance of “FESTAC ‘77” at Lagos City Hall and Wole Soyinka’s lecture at the festival colloquium. But in between we travel freely, for an hour, across time zones. In there, Jayne Cortez would perform “US/Nigerian Relations,” repeating the line “they want the oil, but they don’t want the people” to the backing of free jazz. In that line, there’s the question of what and who can move, the perennial question of the circulation of Black peoples in our world. But underneath her, there’s a gloating radio report from the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation on rising oil prices, which is a comment on the 1973 oil crisis that made FESTAC possible in the first place. All of these histories come together inside a 40-second piece. Rather than seeking to present a coherent whole, we wanted to find new ways of bringing the fragments together and allow the whole to be determined by time limit or page count.