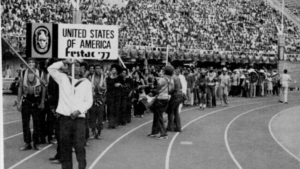

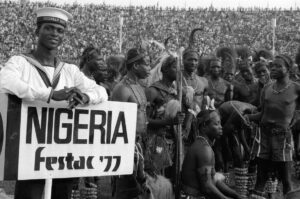

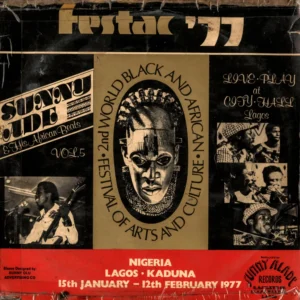

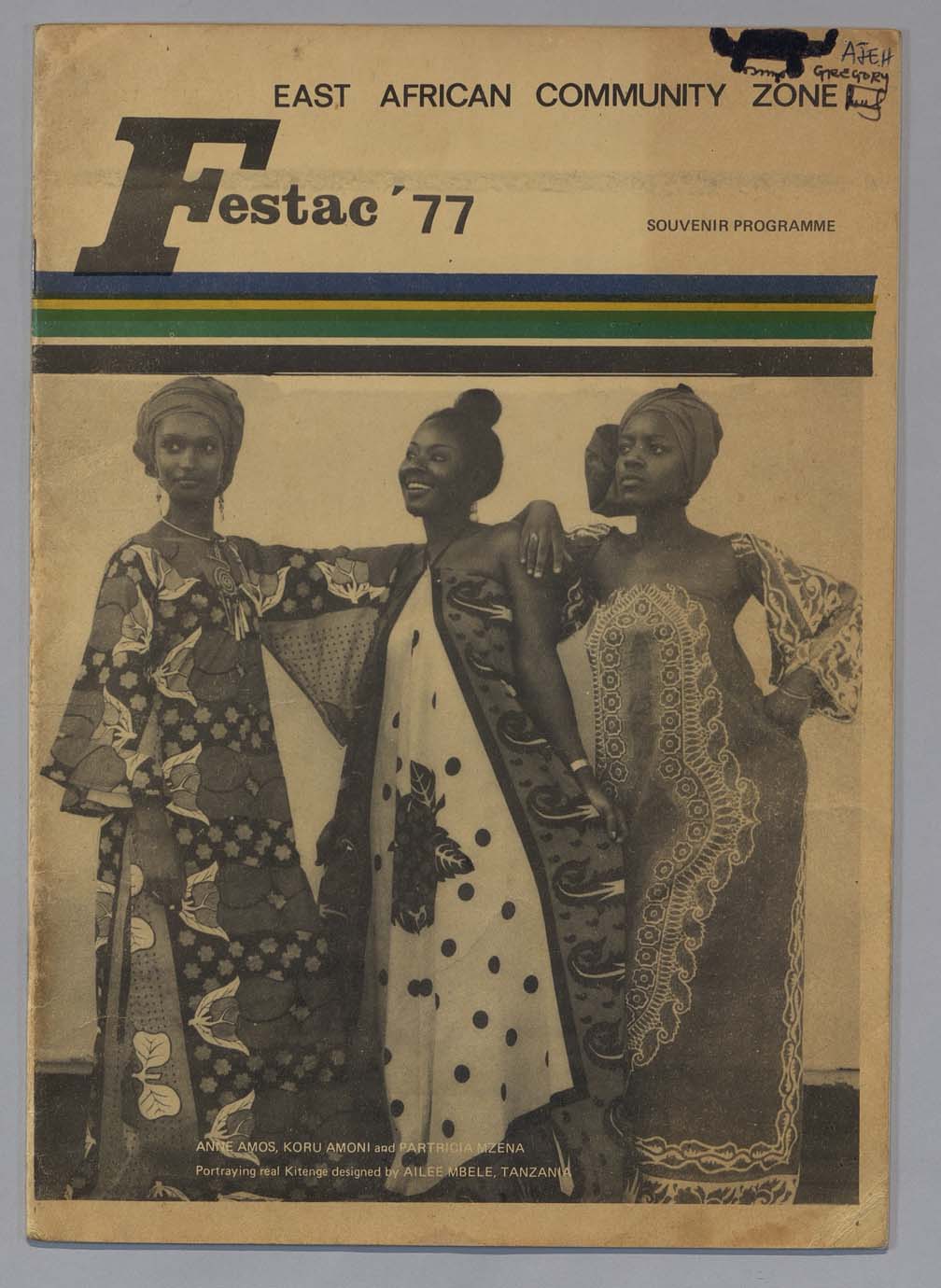

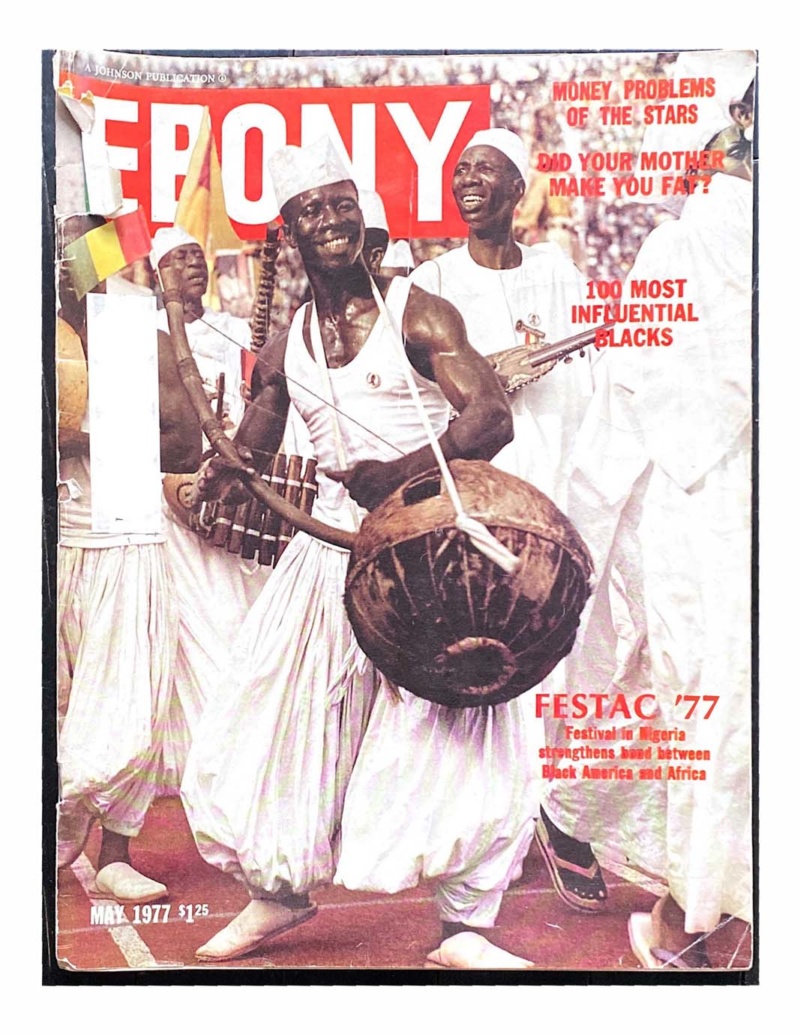

These words, from the May 1977 issue of EBONY, are what famed journalist Alex Poinsett used to describe the participants of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, best known as FESTAC ’77. From January 15–February 12, 1977, more than 15,000 Africans and people of African descent from over fifty-five nations gathered in Lagos, Nigeria to celebrate, share and be in community around varied cultures and art forms. They convened to (re)claim space, significance and influence. Thousands came together to create and reimagine a Blackness that was defined by people of African descent on their own terms, and more expansively than ever before.

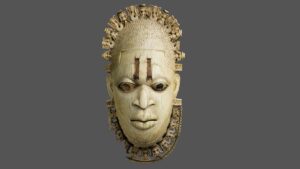

FESTAC was originally scheduled to occur in 1971, as a follow-up to the much more narrowly defined First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal, hosted in 1966 by then-president Léopold Senghor, who believed strongly in Négritude. In what would become an eleven-year gap between the festivals, a number of government upheavals occurred across the Black world: a three-year civil war in Nigeria was fought and a series of other setbacks transpired. Yet none of these deterring forces could stop this historic event from happening. The funding and staging of the festival was controversial as well; the justification for Nigerian head of state Lt. General Olusegun Obasanjo’s decision to spend massive amounts of money and resources was regularly questioned from within and outside of the country, a concern to which he continually remarked that there could never be a cap on the expense or value of bringing together African and African-descended peoples.

We can talk about the politics of this event in terms of actions on the level of government, and that is an important discussion that a number of thinkers and students of history have engaged, but it is also worth focusing on the broader impact of art and culture for FESTAC’s participants and attendees, too. Are art and culture not often embedded in politics, and arbiters of it?

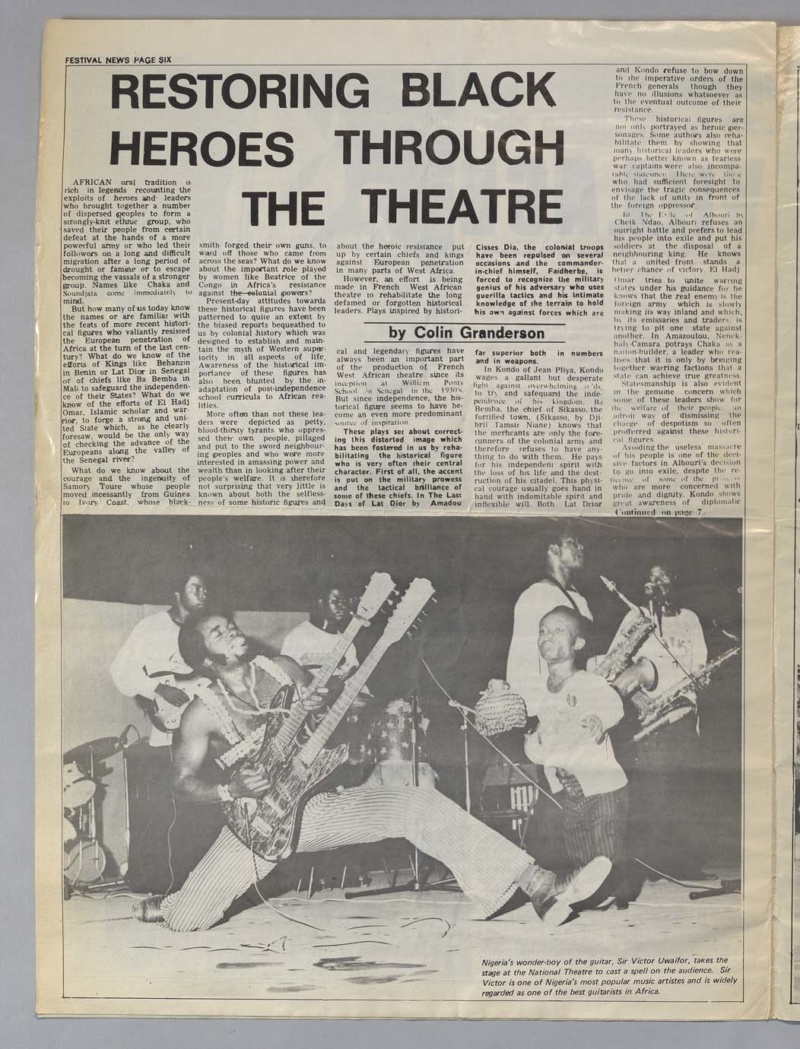

FESTAC ’77 provided an opportunity like no other for African and African-descended creatives to congregate as a means of potentially working through difference and strengthening, as well as establishing, bonds where possible. How could new styles and fusions of music, fashion and art not emerge from such deep wells of creativity and imagination after the collision of so many Black cultures? FESTAC provided the space for Black people from many walks of life to make connections through the creative practices and traditions they had learned to honor and take pride in. From children to elders, those twenty-nine days were filled with back-to-back displays of some of the greatest forms of art, thought and performance ever known. Dance companies. Theatre troupes. Painters. Sculptors. Singers. Academics. Musicians. Photographers. A spectrum of Black artists and artistry. The participating national and diasporic delegations at FESTAC brought some of their most talented artists to show love for their Blackness, in the multitude of ways they’d come to cherish it.

Black newspapers and media in the participating countries produced all kinds of descriptions, critiques and excitement around the festival in the years leading up, during and after. Stories of affirmation, and of being deeply impacted and influenced by experiences of the genuine diversity of Blackness within the delegations, were abound, as were critiques about the effectiveness of this gathering and how to rationalize, for example, the simultaneous occurrence of FESTAC with the other ongoing struggles such as apartheid in South Africa. Unlike the largely racist and diminishing reports from white media outlets, these Black publications, channels and stations offered more detailed, thoughtful, contextual and honest coverage.

For the United States, it was the largest cohort, at that time, of African-Americans to travel to Africa since the forced migration across the Atlantic Ocean via the West African Slave Trade that had moved enormous groups of people in the opposite direction. Bonds were formed in ways that surely words cannot fully describe.

In the era that FESTAC occurred, there were a number of Pan-African festivals organized across the continent in the name of promoting this worldview. It would be remiss not to place this event within that context and understand that FESTAC existed within a constellation of gatherings in service of promoting and preserving Black unity. Today, there are numerous festivals and gatherings that celebrate Black art and culture, with far reaches within Black audiences around the globe. None, though, have accomplished what occurred during those twenty-nine days in early 1977. And, of the thousands of people who participated in that global celebration, there are a few who we can take a closer look at, here in this written space.

Renowned artist, dancer and theatre instructor, Bob “BJ” Johnson (1938–1986) attended FESTAC as a member of the legendary jazz musician Sun Ra’s Arkestra. At the time, Johnson was a young faculty member of the then-emerging Black Studies Program at the University of Pittsburgh, where he taught dance and theatre arts workshops. Johnson also danced with some of the best companies of his time, including an international tour with Katherine Dunham’s company and under Alvin Ailey. It was through Sun Ra’s invitation to be a part of the US cohort that Johnson was able to join a delegation of Black artists and culture makers hailing from more than twenty states all over the US and ranging in age from young people to seasoned creatives in their seventies.

Throughout his time in Nigeria, Johnson kept a sporadic journal and took many pictures to document his experience. What is clear from his personal writings is how profound of an impact FESTAC had on him, to be emerged in a place where he saw what he recognized as the “archetypes” of the faces and mannerisms he’d come to love and recognize as familiar back “home” in the US, amongst the Black communities he’d grown up in. From Johnson’s archive, it’s clear the experience left a deep mark on him and his ability to better understand what it meant to be in the African Diaspora, and how that all came to be. Through his career as an artist and as founder of the Pittsburgh Black Theatre Dance Ensemble, as well as his work with the legendary and now-retired Kuntu Repertory Theatre in Pittsburgh, Johnson situated himself firmly within the Black Arts Movement of the late ’60s and mid-’70s. His experience of FESTAC affirmed him in his dedicated artistry to promote Black consciousness and liberation. Johnson attended much of the festival’s programming (formal and informal) and spent time in community with artists from other delegations, as well attending additional local events in Nigeria to further extend his ability to connect with and understand Black people. Among him, also in the US cohort, was another young artist on her first trip out of the country, and with a big responsibility to maintain.

A young Brooklynite and, at the time, a student at the Institute of New Cinema Artists in New York City, Marilyn Nance served as the US contingent’s official photographer. Nance was initially admitted to the cohort as an exhibiting artist, but was later uninvited as a result of a reduction in the budget and size of the contingency, after years of delay. But, being the determined person she was, Nance found a work-around and applied to be employed as a photo technician instead. She was hired and ultimately assigned to be the official photographer for the North American Zone (the festival was divided into world zones and the US was included in this one). Originally only slated to attend half of the festival, Nance decided to stay for the full month of programming; this once-in-a-lifetime experience left her with an archive of over 1,500 images, some of which can be found on her Instagram page dedicated to FESTAC (@festac77archive) today.

Like Johnson, Nance was moved by her experiences with so many parts of the African and Black world present for the festival, and her time in Lagos affirmed her values as they related to the Civil Rights and Black Arts Movements she emerged from. In a 2017 interview for Africultures, Nance illustrated the vibrancy of the atmosphere at FESTAC when she explained that because she did not have a telephoto lens, she was “right up in people’s faces… They were present for me as I was present for them… an intimacy—a strong desire to know more about each other.”

Though there was no permanent organization or entity established to continue the work and legacy of FESTAC upon their return to the US, many artists like Johnson and Nance developed their artistry and shared their stories with the communities they returned to, as was intended by late Howard University Professor Jeff Donaldson, the North American Zone’s director and coordinator. A number of reiterations and spinoffs would be organized on much smaller scales well into the late ’80s. None of them would be on the scale of the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture.

By no means was FESTAC ’77 perfect. With over a decade’s worth of delays and controversy leading up to and after it, there is still much to learn about the lasting impact of this event. Fortunately, entities such as Chimurenga, a Pan-African arts, media and politics platform based in South Africa, have taken on the task of preserving the legacy of FESTAC ’77 through their dedicated publication of the same name that chronicles the journey of this festival, as well as the platform’s public programming about this event in various parts of the world.

Much of what is left to remember about this unforgettable gathering is still in the hearts and minds of the people who attended it, many of whom are transitioning into ancestral realms, as they have grown older in the over forty years that have passed since that memorable period of twenty-nine days, taking these stories with them. May we continue to connect and commune with the work and memories of Marilyn Nance, BJ Johnson and the thousands of African and diasporic artists and culture makers who convened that month in the name of many purposes, but most certainly, of Black joy.

Where and how we exist, as Black people, is vast. There is no part of the world without us and yet we continue to be reduced in the public eye. What happens when, instead, we turn the cameras onto ourselves and each other? What happens when our art and culture are given space to be shared and cultivated, as we have inherited and innovated them?

Black joy invokes a we—a collective experience that can offer inspiration, imaginative thinking and, at its best, healing. The type of healing that fortifies us and regenerates the ability to create a world that loves us back as much as we have love (in)to the world. Axé and deep gratitude for all that has been done and will continue to be done in service of preserving and cultivating our joy as a means towards liberation.